In the winter of 1991, snow was everywhere: on the roads, on top of cars, on the roofs of houses, on the trees and grass, on the park benches, in the hearts of young children pulling sleds, in the thoughts of the employees of the road maintenance department, and in the fat pockets of the ski resort managers, although the white and pure could not cover the grayness of the dull and ugly apartment buildings, the ingrown soot caked in the chimneys, the broken arms of old ladies who slipped on ice while purchasing their daily oblation of bread and milk, the excrements flushed down from the poo-poo seats mixed with toxic chemicals from the precious metal processing plant, which together flowed straight into the scrawny river that cut through our undistinguished town, nor the place where innocence was eviscerated from the hearts of those who ceremoniously gorged on the flesh of humble animals, boozed alone early in the morning, swallowed cigarette smoke before brushing their teeth, and savored a quiet and controlled depression arising out of boredom, lack of proper guidance, and a general absence of meaning in life.

It was midday when I met with a friend in the snow-covered park stretching through the center of our town. Do not ask how I knew he would be there, without mobile phones to text each other or a map cutout marking the exact location where we stood. I also do not remember how we found out there was a concert by my teenage paragon, a musical Bodhisattva and a human daemon—named Iggy Pop. We just knew. A miracle!

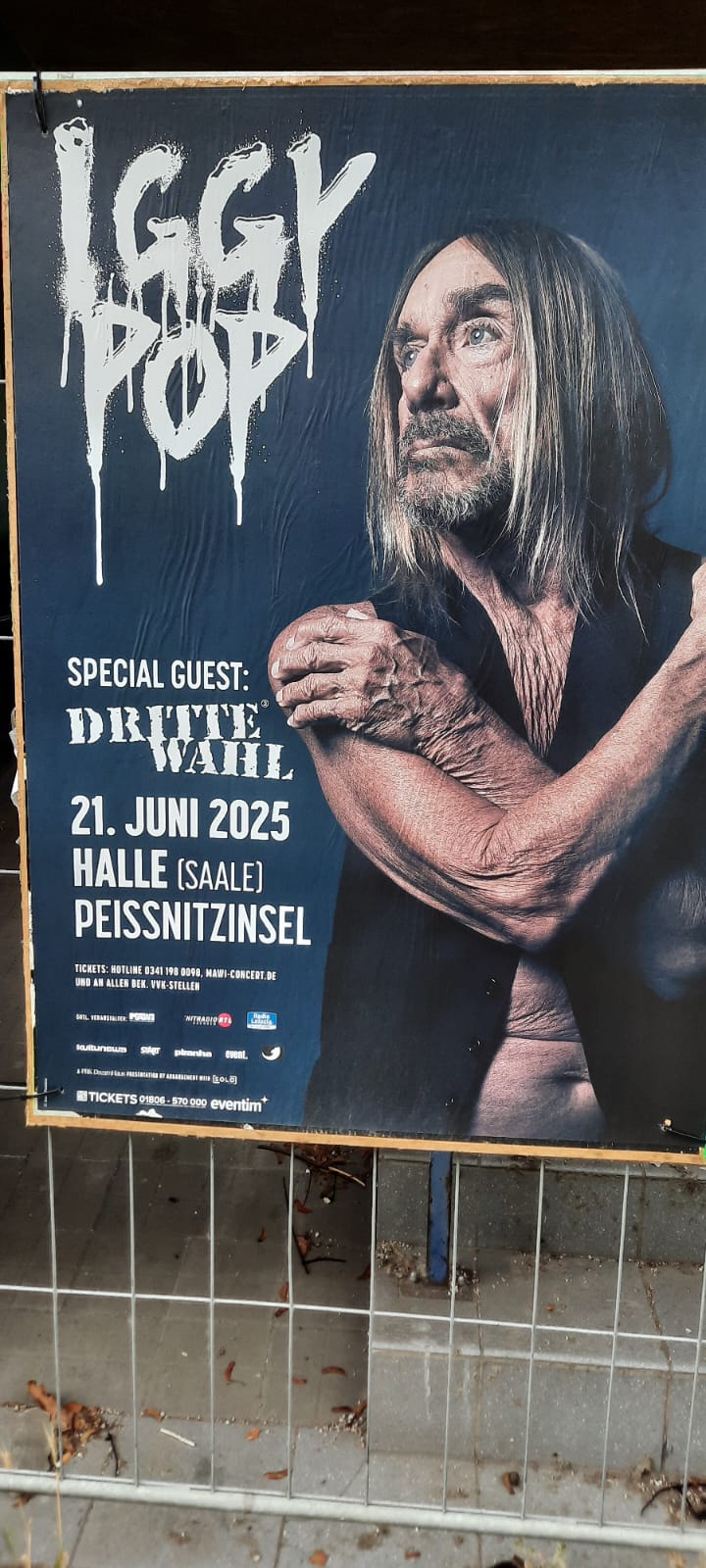

We wanted to go see Mr. Pop but were short on money. The first obstacle was covering the trip to the state capital. We devised a strategy: we planted ourselves in front of the train station and asked people to share part of their money with us because we wanted to see this great personality who would grace our land only once in a lifetime. People appreciated the honesty, some pitched in a few coins, some gave a banknote. After freezing for several hours, we had enough for the train fare. Our bodies, particularly our toes, relished those four hours in an overheated, slow-galloping train. In the big city, we stood next to the thick pillar used for plastering posters, several of which showed the perfectly carved torso of Iggy Pop.

“Excuse me, can you help us buy tickets? We want to see this man today. His name is Iggy Pop. It is very important to us.”

Our toes went numb again. We, of course, did not care. When you are young, you can voluntarily—and with gusto—turn your back on any of life’s comforts and conveniences to accomplish what is meaningful to you. Revolutions have been started by young men and women who risked, even lost, their lives. I did not mind the begging, the ice, the numbness. I wanted to see Iggy. It was special to me. This concert would mark my last conscious effort to grossly gratify my senses in this lifetime—something like the last cigarette while standing in front of the death squad, or the farewell hug to your dear ones before being drafted to the war zone.

We got enough money and went in. It was a blast. Iggy delivered. Shirtless, he wiggled and spun, jumped high, sat on his knees and bent his back all the way to the ground, unbuttoned his jeans and let them slide down his thighs, pointed at a group of girls, and said something. Every minute, he fired more energy and exuberance into the audience. When he sang “Real Wild Child,” everyone really went wild. I merged with the mass of ten thousand bouncing admirers and danced, leapt, and shouted. Time stopped. It was a terrific evening. As a bonus, after the concert, we were invited to a party at someone’s house.

Iggy Pop had been my teenage idol. I admired his nonconformism and unhinged performance on stage. His noted lines—“Everybody always tryin’ to tell me what to do. Don’t you try to tell me what to do”—encouraged me not to care what others thought, and especially to shun the formulaic life followed by the people of my small town. It was a one-way street with no return: they went to school, got a job, got married and produced kids, waited to get grand kids, watched a lot of TV, believed everything they saw on TV, and honored newspapers as the source of absolute truth, they washed their cars, worked more, talked about their jobs, went on a ten-day vacation, spent the rest of the year reminiscing about that vacation—and in the end, they died. I wanted to find out if there were other trails to tread.

When I began listening to “unconventional” music, I proudly thought I had stepped out of the rut, that I was alternative and progressive. Soon, however, my balloon of illusion deflated. I realized I was just like anybody else: sexuality was still at the top of my priorities, money and material comforts were my utter needs, and societal status was an important goal in my strivings. How was that any dandier than “their” lifestyle? Even the most uneventful and unimaginative person desired these same things. Indeed, even animals wanted them.

As a teenager, I idolized people who were extreme, had atrocious behavior, and who abandoned the norms of the society that everybody so blindly obeyed. Although I was not remotely disorderly or rebellious, I kept observing what those patterns were and what the consequences of breaking them might be. I noticed that the unorthodox people replaced conformist lifestyles with outwardly more colorful and frolicsome ones, but the essence of it was still the same. I wondered: if I stepped out of both worlds, where would I end up?

Gradually, I gave up on society altogether, even the music I listened to, the books I read, the humor I laughed at, the life’s tenets I lived by, they all were demythologizing themselves before my very eyes. In my heart, I became anti-people, anti-towns and villages, anti-planet Earth, anti-Universe, and anti-sound, space, and time. I had reached negative Nirvana. This antagonism gave me mostly frustration, discontent, and a tenuous dose of pessimism. The days were gloomy, the nights sleepless. Inside the tunnel, it was pitch black.

Then, it lit up.

A friend of mine gave me a book his mother had bought “somewhere,” although she had not intended to. He tried to read it, it was not an easy read, so he offered it to me because I “liked the weird books.” The title read: Srimad Bhagavatam: Third Canto. In a few days, I devoured the text. When I closed the last page, I could only agree with the statement that the Srimad Bhagavatam is the beacon of light illuminating the darkness of our times. The knowledge inside is a treasure because it offers genuine guidance to all those like me, who are, to varying degrees, disillusioned with the world. It gives a perfect analysis of material conditions and, at the same time, presents spiritual solutions. Finally, I was getting wind at my back.

After closing the last chapter of Srimad Bhagavatam, it was clear that my materialistic life would soon end. But what was next? I knew I was about to step into the uncertain, the uncharted—but I was ready. The call from the spiritual world was enchanting and, to me, very real. I underwent a genuine spiritual awakening. The book discussed many significant issues. I learned that it is an illusion to think that my body is me; rather, it is a vehicle that carries the soul, which is my real identity. The awkwardness I felt was not surprising, because for a soul to be in the material world is unnatural. Material life limits my freedom and exposes me to all kinds of sufferings and uncomfortable situations that are, in actuality, unnecessary. Bodily pain—both physical and mental—is equally useless and purposeless. The only value in life’s distress is that it can potentially inspire me to think about spiritual matters. I needed torments and inconveniences to remind me that I do not need them.

Steeped in illusion, I had considered the unremarkable township in the forgotten hills my home, and the aggregation of several mountain ranges and valleys, my country. Together with other befuddled souls entrapped in their bodies, I squeezed to my chest a piece of cloth with “my” land’s distinctive colors, and I sprang in delight when “my” group of grown men managed to place the air-filled round object into the net attached to the three wooden planks at the end of the grassy field.

I also thought that numbing my consciousness by inhaling the smoke of a burned dried plant—thus artificially creating episodic euphoria in my brain—was what it meant to have a “good time,” and that only sequences of other, equally simulated “good times” could constitute an optimal Friday evening. At the forefront of all stood sex—the Goliath of indulgences, the mighty locomotive propelling everyone’s mind, speech, and variety of endeavors. It was the ambition and aspiration of all men and women, and although mostly unspoken and hidden within hearts and minds, it was always lurking, anticipating, and hoping the next amorous conquest was nigh.

To reach that end, I had to have money, because money brings dwellings, cars, trinkets, clothes, and tons of prestige. These shiny items glitter in the eyes of the opposite sex, clearly relaying the message that I am well supplied and therefore worthy of receiving intercourse. This entire circus reminds me of a peacock repeatedly spreading his psychedelic tail in front of the female—ad nauseam—only to impress her. Meanwhile, she carefully observes the feather display, assessing their size, color, and the vigor of the male’s anatomy. At the end of the three-month-long mating season, the peahen decides with which muscle man she will have offspring. After the routine is over, all is peaceful for the next nine months. Sadly, humans keep on being ridiculous 365 days a year.

It is explained that the pleasures of this world are pale in comparison to spiritual bliss, like water in a calf’s hoofprint beside the body of a mighty ocean. Material joys, as well as the bodily lifespan, are limited. The forms we acquire in the spiritual world are eternal; they are not covered by ignorance, and the subsequent enjoyments are not subject to fluctuation. Moreover, we will associate with many other wonderful and free souls and together interact with Krishna, God, in various ways. We could admire Him from a distance, relishing His form and appreciating His majestic features. We could assist Him personally, accommodating His immediate needs. We could be His friends and relate intimately. We could develop parental affection. And at last, we could become a lover of God. These five types of relationships may sound fantastical at first, but by immersing oneself in devotional practices and learning about the nature of God and His creation, they begin to make sense.

Perhaps I was foolish and naive back then, but the idea of becoming a Hindu monk, whatever that might have meant, was appealing to me. I had no pious background: neither I, nor any of my close family members, nor any friend, nor anybody I had ever met was religious—my grandmother being the only exception. God was remote and unknown. Nobody talked about Him, nor was anyone interested in the subject. Yet after reading that ominous book, I was bewitched by the information I found there and started to believe that Krishna is the “Supreme Personality of Godhead,” and that my constitutional position was to serve Him.

Historically, I had changed body after body, and in my forgetfulness of the previous one, I always thought that the current bodily frame was all in all, and that my primary objective was to satisfy its wants. By doing so, I only entangled myself and sank deeper into the complicated maze of reactions to my actions—karma—then was born and died again, without ever knowing why I lived or what the purpose of my existence was.

The next practical step was to slowly relinquish the brakes impeding my spiritual progress. The girl I was seeing could not understand why celibacy was necessary, my drinking buddies thought I had lost my mind, and my parents were most amused when I began to “cook” for myself. I had become a vegetarian, a habit so foreign to my townsfolk that everyone thought I would shrivel up and turn into a walking mummy within weeks. I paid no heed. Cooking usually meant I burned the pot while attempting to prepare rice, or let oil overheat trying to fry potatoes. The only decent dish I could make was halava—a mixture of semolina, butter, and sugar. It tasted good, but after a month, it was crushing my stomach from eating it every day.

Besides the compulsory habit changes, I began to read, speak, and listen to the words and sounds glorifying Krishna and His abode. I added the Bhagavad Gita As It Is to my reading list, which, along with the Srimad Bhagavatam, had been rendered and expertly commented upon by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. I also murmured and sang the Hare Krishna mantra. Hare Krishna was everywhere. I wrote the words on paper and posted them on the wall. I spoke about it to my friends. My cassette player tirelessly played the one tape I got from a hippie who had been to India and knew the Hare Krishnas.

It was not all roses, though. With many ups, but also several downs, it took me almost a year to reach the stage where I was ready to give it all up and move to a Krishna temple, to live with other people who wanted to abide by the same doctrine. It was a brave step, a risky step, certainly not applauded by any member of my immediate social milieu. More than that, I was doubtful if I would make it. All of us are entrenched in this world, attached by the deep roots of desires and hankerings. The ideals displayed in the Srimad Bhagavatam seemed unattainable—at least for hotheads with my background. But, then again, the urge to explore the “other side” prevailed, and I went for it. Before the departure, I wanted to draw a line: the day Iggy came I chose to be my last voluntary participation in the folly of pretending to be the Almighty in a world where—besides a few rare felicitous moments—I had mostly been kicked and dragged aimlessly by my unbridled senses, like a bull pulled by a nose ring. That concert stands as the turning point in my own commitment to serious spiritual practices.

I invite readers to set time for their own Iggy Pop show, after which they too will leave material creation behind and venture toward a better alternative—into the spiritual arena under the tutelage of Krishna—where bliss and knowledge eternally shine.